Palos Hills was incorporated as a city in October, 1958. The generalized boundaries of Palos Hills at incorporation were the Calumet-Sag Canal, 95th Street, Kean Avenue and Harlem Avenue.

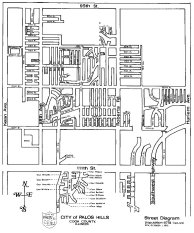

You can click on the map to the below for a larger image of the generalized boundaries of Palos Hills.

Origin of Palos Hills Name - Incorporation of Palos Hills

(Excerpt of Article Thursday, March 7, 1974 Palos Regional Newspaper)

"The name Palos, like the names of many towns and cities across the United States, has its origin in the Old World. Palos is the namesake of Palos de Frontera, the port across the sear from whose harbor sailed the Nina, the Pinta and the Santa Maria.

When the township was first organized in 1850 from a part of the old York precinct, it was named Trenton. Soon after this time, however, officials learned that another Trenton township was located nearby.

Reputedly, the name Palos was suggested by Melanchan Powell, one of the earliest settlers and first postmaster of Palos. Powel, drawing on a family tradition that one of his ancestors had been a member of the crew on one of the ships commanded by Christopher Columbus, suggested the name Palos. Though the exact translation of the Spanish word "Palos" is uncertain, it may mean a tall tree, a mast of a ship, or a promontory.

The building of the Illinois-Michigan canal brought swarms of settlers from Germany, Ireland, and the eastern United States to the area. Soon after these people arrived, the woodchoppers, the farmers, and the stock raisers came to live in Palos.

The "Hills", the "Park", and the "Heights", were added to the name of Palos by real estate developers."

Palos Hills was predominantly a farming community until World War ll when the Chrysler Corporation built an airplane factory at Ford City, and land developers discovered the area known then as North Palos. Soon after the war's end, commercial home building in the areas began, and in 1946 the first Fire House was erected. The first school in North Palos District 117 was built in 1940.

In 1957, it became apparent that Hickory Hills, Worth, Bridgeview, and Chicago Ridge were gradually extending their boundaries into North Palos. It was time for some action to be taken towards a charter and the North Palos Community Council was formed with Earl Potter chosen as president. A referendum was held on October 25, 1958 at which time residents voted to incorporate the city of Palos Hills. Soon after the referendum passed, Carleton Ihde was elected the first Mayor.

Since that time the city has grown considerably, bringing to the community the Green Hills Library, A.A. Stagg High School, and Moraine Valley Community College, and various churches and schools, as well as numerous businesses.

In the Early 1980's, Palos Hills began a new City Administration under the leadership of Gerald R. Bennett as Mayor. Many major improvements have been made since this time; including new roadways, drainage, improved sidewalks, lighting projects on our main thoroughfares and neighborhood streets. We've also seen the addition of a municipal golf course, expanded park services and a community resource department serving the needs of all age groups. In 1994, a new City Hall at 10335 South Roberts Road was dedicated which houses the departments of Administration, Sewer & Water, Building and Licensing, Community Resources and our Ordinance/Animal Control Officer.

Palos Hills - A Pre-History

by William L. Potter

(All Rights Reserved - Copyright William L. Potter)

(Excerpts Reprinted With Permission of Mr. William L. Potter)

Requiem In Palos Hills

She came with her family to spend the summer here one year. While others in the family hunted in the nearby woods and fished in the Sag, she gathered berries and helped her mother in the garden. She loved it here. Autumn came; her family moved on, but she never left. When she died, they buried her on the wooded hill behind the garden. That was over 250 summers ago. The girl's body still lies undisturbed and undetected in the yard of a home in Palos Hills. The girl was an early resident of Palos. She was an Indian.

The Indian Pioneers In Palos

For thousands of years, Indians were attracted to this area, establishing camps and small village sites along the Sagaunash Swamp. This grass choked body of water and mud stretched from the Des Plaines River valley on the west to what is now Blue Island on the east. The Sag swamp had the features primitive man looked for: the watery areas held a bountiful supply of fish, clams, birds, and fur bearing animals. The shores of the Sag (and nearby bogs) were dotted with plants that provided numerous edible roots and berries; the rich soil was suitable for growing their crops of maize, beans and squash. The nearby hills and woods provided game such as deer and raccoon. Rivulets, intermittent streams, and springs at the base of those hills provided fresh water. In short, the Sag Swamp area was one of several locations in the Chicago area that Indians sought out while in the vicinity of the tip of Lake Michigan.

The Arrival of the Europeans

Late in the summer of 1673, Louis Joliet and Father Jacques Marquette paddled their canoes up the Illinois and Des Plaines rivers, then portaged to the Chicago River, and pushed on to Lake Michigan while returning to Canada from their journey of exploration. And in so doing, they moved the Illinois Country out of its pre-historic status. The written history of Illinois had begun. It is possible other Europeans had been in the area prior to this, but if so, they made no attempt to record the fact. The historic Period (1673 to the mid 1830's for Indians in Illinois) was the era of contact with the white people; the explorers and Voyageurs, the Coureurs de Bois (the French "rangers of the woods" who conducted extensive though illegal trade with the Indians), the Habitants (French settlers establishing small, villages in the wilderness), the soldiers of France, Great Britain, the United States, and even (in one instance) Spain, and the American settlers entered the Illinois country and influenced the Indian way of life. It was a period of rapid erosion of native culture. White traders brought in large amounts of trade items, all vastly superior to any equivalent items produced by the Indians, and gradually saturated the Indian life style to such an extent that their native skill and crafts fell into disuse. Iron axes replaced those chipped or ground from stone, brass pots replaced native pottery, while fine European cloth replaced animal skins and rude native woven cloth. The rush to adopt the new technology available to them and the shunning of their own stone age technology resulted in an increasing dependence by the Indian on the white man, which in turn resulted in an increasing dominance of the Indian by the Whites. Not all the Indians went along with their increasing subservience. Revolts, in Illinois and the Midwest, against white influence did occur, most notable being the Fox Indians. against the French in the early 1700's, Pontiac's Rebellion against the British in 1763, and the Blackhawk War of 1832. The latter was more the product of white fear than Indian threat, but it did seal the fate of all the Indians still living in Illinois: legislation was enacted to move the remaining tribes (many had already gone on their own) west of the Mississippi. The principal removal was from the Chicago area (where several tribes had gathered to receive Government handouts and await the move) in 1835, with residual groups being removed through 1839. Thus ended the Historic period for the Indians of Illinois.

Indian Sites In Palos Hills

Two Indian sites have been excavated in our area by archeologists. The sites produced artifacts that indicate Indians from each of the above described periods visited: here, but the two sites were occupied principally by Indians of the Upper-Mississippian and early Historic periods. This doesn't eliminate the possibility that village sites from other periods might have been here. Palos Hills and the surrounding area were dotted with archeological sites at one time. Farmers in the 1900's often struck graves with their plows, and they collected arrowheads and other artifacts literally by buckets-full. Many of these sites have been totally obliterated by the construction of homes, roads, and sewers; the information that might have been obtained from these sites is lost forever. Other sites have been disturbed or partially destroyed by farming; construction, and robbery by "pot-hunters," inept or irresponsible amateurs who dig carelessly at sites to bolster personal collections, often losing important data in the process. Such sites are still valuable sources of information (although somewhat garbled); but are unfortunately passed over by professional archeologists who, in consideration of the small quantities of money available for excavations, must go on to the sites that will produce the most information. There are undoubtedly a number of sites in our area that have gone undetected; for this reason, you should report any artifacts you may find so they may be recorded. The two sites excavated nearby were the Knoll Spring site near Palos Hills City Hall, and the Palos site near the model airplane field on Route 45. The first was excavated by Charles M. Slaymaker III from Treganza Anthropology Museum at San Francisco State College, the latter by members of the Field Museum’s Summer Anthropology program.

Indian Methodology and Hardware

What's found at Indian sites in our area? The most common items are flint flakes and fire-cracked rocks. Flint flakes were a by-product of making flint tools such as arrowheads. The first step was to find a suitable nodule of flint or chirt, glassy rock material that would break into long flakes when properly struck. The nodule would be broken away until a core remained, which was discarded. The best pieces were chosen for further working. Striking a well-placed, glancing blow to the larger flake produced a smaller one. A hundred other skillful strikes would produce a useful article and hundreds of flakes. A misplaced blow would produce a broken item which, if it couldn't be converted into some other tool, was discarded. A skilled flint shapper could produce a projectile point or other artifact in a few minutes.

The fire cracked rock was the result of one method of cooking used by the Indians. A pit was dug and filled with wood and rocks. The wood was burned, causing the rocks to become almost red hot. The coals and rocks were raked aside; fish, roots, and other foodstuffs were wrapped in wet leaves or grass and placed in the pit. The rocks were then pushed back over the food, which was allowed to cook as needed. Heated rocks were also tossed into hides filled with water to boil other foods. The heated rocks usually fractured as a result of such use.

Among the most common flint artifacts are projectile points for arrows, spears, and darts; blades (flints with sharp or serrated edges) used for cutting meat, hide, or wood; drills (similar to arrowheads,. but with a long, narrow point) for drilling holes in hide, wood and shell; and scrapers for dressing hides before tanning. Flint hoes or digging tool blades are found occasionally, as are gun flints.

Common non-flint stone items include ground down ax heads, hammer stones, grinding stones (for grinding corn etc.) and celts (which may have been a sort of multi-purpose tool for grinding and chopping). Occasionally ground stone tobacco pipes are found. Common items made from bones or antlers were hoes and digging tools, projectile points, awls, and needles for matting or weaving. Items made from clamshells included hoes and spoons. Shell was ground up and mixed with clay to make certain pottery items.

Artifacts found here made from natural copper include finger rings, beads, and hair tubes, (long, thin tubes that were formed around shanks of hair as a common hairstyle). The copper was prepared by beating the copper nodules flat with a hammer stone.

Pottery was made from certain clays to which various tempering materials, such as shell or ground stone, were added to increase its durability. It was paddled and kneaded to shape, then fired at a relatively low temperature; the result was vessels that were closer to hardened dirt than to modern ceramics. Each culture had its own particular materials, finishes shapes, and decorations; this coupled with the fact that the easily broken pots were often left where they broke, make them useful tools for dating sites and identifying the cultures.

Indicators of what our Indian predecessors ate while in the Palos area include fish scales and bones, clam shells, bird bones, small animal bones, and deer bones. Remains of stored corn occasionally turn up. White man's trade artifacts that have been found in the area include gun parts, a bullet, bits of brass kettles, iron trade arrowheads, kaolin (white clay) tobacco pipes, glass trade beads, iron knives, iron hatchets, and steel strikers for starting fires. Trade manifests from the Historic Period indicate many other trade items were available to the Indians, but have not tuned up here.

It should be noted the above list is by no means complete

The present overall .view (from data unearthed) of the Indian Villages of the Sag is of small clusters of Indians, probably amounting to 25 or fewer people, closely related to the Upper Mississippian culture, Blue Island subculture (a variation in the culture first recognized at a site in that nearby area). The village was probably a summer camp; virtually all the Indian cultures went to different areas of the Midwest according to the season. Housing was not substantial enough to have left post moulds below the plow level (although evidence of ' long, oval houses have been found at other sites of this culture in the Chicago Area). The presence of relatively few European trade items shows some contact with the whites, but not extensive contact, which would indicate the excavated sites were probable not occupied during the late Historic Period.

Tribal distinctions were first made in the writings of the early explorers. The tribes occupying our area would be difficult or impossible to, pinpoint. However, tribes known to have occupied the Chicago area at various times during the first half of the Historic Period include the Miami, the Wea, the Sauk, the Fox, the Potawatomi (with some of their 0jibway and Ottawa cousins), the Mascoutah, and the Kickapoo. The Illini Indians, for whom Illinois is named, do not appear to have been residents of this area during the Historic Period, although a few winter hunting parties were found starving in the Chicago area in 1674, and a small group may have been living somewhere in the area in 1676

The Marquette Era

While the Illinois country on the whole entered the' light of history in 1673, the Palos area remained in the shadows until the 1830's. This historical gray area has proven to be a spawning ground for local legends and speculations that have come to be repeated as fact; these legends merit some discussion.

One legend has Marquette and Joliet camping or saying Mass in the Palos vicinity in 1673. The basis for this conclusion is probably more wishful thinking than fact. Unfortunately, the records and maps that are cited as proof for this legend are anything but conclusive. Joliet's notes made during the 1673 expedition were lost when his canoe went down; the so called Joliet maps were all drawn after the event, and in fact, were not all done by the same person, causing some confusion in accuracy. Marquette's map of the voyage is virtually without details. All maps from this period show great amounts of distortion that make them useless for pinpointing landmarks. Marquette's account (written after the trip was over) probably wasn't even written by him. The events related in that journal are in many instances vague and subject to broad interpretation. It is interesting to note that many towns have used the very same information to "prove" that Marquette and Joliet stayed in their city. Although there is a slight possibility of Marquette and/or Joliet having been in Palos, there is no way of proving where they went in the Chicago area from the records now available.

Another legend suggests that the Chicago Portage (the route used by the explorers and voyagers of the 17th and 18th centuries to get from Lake Michigan to the Des Plaines River) was via the Calumet River, Stoney Creek, and the Sagaunash Swamp. In 1830, Indian guides for an Illinois Michigan Canal surveyor said that in times of high water, a direct water connection existed between the Lake and the Des Plaines via the Sag route. However, the Calumet River shows up (with any degree of certainty) on only a few maps prior to that time, and the Sagaunash Swamp (also labeled Grassy Lake) doesn't make regular appearances on maps until the 1830's, indicating a lack of importance. Also, proponents of the Sag Portage theory have occasionally based their claims on the same shaky evidence used to place Marquette and Joliet in Palos.

The preponderance of evidence indicates the normal Chicago Portage was the Chicago River, Mud Lake, Des Plaines River route (passing in or near Stickney, Forest View, and Lyons) generally accepted by historians. However, this route undoubtedly wasn't as tried and true as some historians would like us to believe. The actual route probably varied considerably according to season, and it is not too unreasonable to assume that, in light of the comments made by the Indians to the Canal surveyors, the Sag Swamp may have been used as an occasional alternate route. But for the bulk of the 17th and 18th century traffic, the Chicago Portage was where it was supposed to be.

The French Skeleton

Another legend states that in 1858, Thomas Kelly of Section 18, Palos Township, found "the skeleton of a man with an ancient French gun and copper powder horn, with the inscription `Frary Brinhem' etched upon it". Just how it was determined that the gun was French is not known; it is very unlikely anyone but an expert could examine a musket excavated after decades of exposure and tell if it was a French one. Indeed, many of the American military muskets made up until the early 1800's were copied from earlier French weapons. Some French soldiers did have brass powder flasks, but the one found by Kelly would have to be compared with existing samples to produce any meaningful information; the flask could easily have been from one of several periods of time and places of origin. Unfortunately, the Kelly finds probably no longer exist or are not available for examination: Several sources give accounts of the Kelly, fords, which indicates he really did ford a skeleton, gun, and powder flask. The man probably was alone at the time of his death, and possibly died of natural causes; if he had been with companions or had been killed by hostiles, his weapon and powder probably would not have been left with the body. Who he was, what he was doing here, and the year of his death may never be known.

A legend closely related to the above is that of caches of French and Spanish coins turning up in our area; the stories go that these coins were left by soldiers, explorers, etc. One must wonder what these people would have used coins for out in the wilderness, and why they would have lugged them so far to bury them. more probable explanation could lie in one of the periods in the 1800's when foreign coinage was in use because of shortages or distrust in American money. Another explanation might be the caches were left by immigrants who flooded the area in the 1840's. Of course, the key to the mystery lies in the coins: when and where they were struck. The coins that were supposedly found haven't been produced for examination, and there was apparently no attempt to record or report any inscriptions on them: Perhaps some relative of those who found the coins might still have them, but verification of their authenticity would be a problem at this late date.

A few longtime residents have claimed that members of their families had dug up "French" swords, "French" lances, and "French" guns while plowing in days passed. For a time, it seems, every piece of rusty metal hit was a "French" something. It is possible they really were the items they were claimed to be; they could even really be French. However, none of the items have ever been produced for examination, so their authenticity will never be proved or disproved; even their very existence must (for now at least) be put in the "legend" category.

All of the above legends have been treated in a somewhat pessimistic light. However, there are some flies in this historical ointment, anomalies that create more questions than they answer.

The French Forts

In the 1830's, visitors to this area found the remains of what were apparently earthworks fortifications on the bluffs overlooking the Sag Swamp. Although there is some confusion in a few early descriptions, there were apparently two fortifications, one on or near the site of Palos Hills City Hall and the Green Hills Library, the other near the intersection of 107th and Kean Ave :

All traces of the earthworks were destroyed by farming and road building early in this century, so we are reliant upon a handful of descriptions made near the turn of the century. One person wrote he had first visited, one of the sites in 1833, and had revisited it several times before his 1883 writing. He described the earthworks as having trees at least 100 years old growing within their confines, making it doubtful the fortification was built in the 1800's. The fort he was describing was probably near Kean Ave., but there is a sizable discrepancy between the location he gives (near the Model Plane Field on Rt. 45) and the location given by contemporaries who were reprinting his letter. It is interesting to note that he casually suggests the earthworks were possibly the, work of French explorers. This supposition has "poisoned the well" with writers after him taking the hypothesis as fact, thus creating a French heritage for Palos that may or may not be true.

The Palos Hills Cannonballs

It would seem logical these forts were of Indian construction, especially considering their close proximity to Indian village sites. Fortifications are common to several Indian cultures. The City Hall earthworks were described as being square and about 200 ft. long. Circular and square platforms are common in Indian fortifications. However, the fortification purported to be near 107th and Kean was described as triangular, not typical of Indian forts, but common to European construction. Then there is the matter of the cannonballs: In 1963, children found three cannonballs embedded in the bottom of a freshly cut ditch at 87th Avenue and 103rd Street, a block west of one of the probable fort sites. Another was found 1/4 of a mile northwest of there lying on the ground. A fifth has come to light that had supposedly been found "East of Willow Springs" about sixty years ago.

The sizes of the cannonballs are 1-17/32", 1-9/16", 2-1/8", 2-1/2", and 2-11/16" in diameter. The first two correspond almost exactly to the size of British ordinance 1/2 pound shot used in swivel guns (small cannons often mounted on ramparts and ship's railings). This size was used by several nations, including the U.S. in its early days. The next size is also in the swivel gun class and is probably a "one‑and‑a‑half pounder". The fourth is a 2 pounder near (but not quite) to British specs. Again, several armies used cannons firing a ball this size. The fifth cannon ball comes closest to matching the theoretical size of a French 2 pound gun. It should be noted that cannons were usually identified by the weight of the iron ball they fired. In viewing the above information, it is important to realize there was considerable variation in the size of cannonballs for a single caliber gun; this size difference results from poor casting or inaccurate moulds but was acceptable as long as the shot fit freely and easily down the bore of the gun. Because of this size difference in shot, because of the common use of similar size cannons by several countries, and because of the practice of using captured weapons, it would be very risky to base any conclusions on the size of the cannonballs found. However, each of the sizes found were obsolete by the Civil War Period.

These cannonballs present more questions than they answer. Palos. Hills and the surrounding area has no documented military history, or at least any that has come to light. How did the cannonballs get here? Are they related to the fort sites, or is their presence coincidental? Were they all left during the same period of time? If so, how come there are so many different sizes involved? Perhaps there was some sort of military action here that has been overlooked by historians. Is it possible? Several military expeditions, including French, American, and English, are known to have passed through the Chicago area in the 17th and 18th centuries, although it would be difficult to pinpoint their exact routes. If one of these groups were here and built a fort, it would have been a temporary field fortification that was to be occupied for only a short time. But why haven't more military items been found? Could it be the artifacts the old timers were rumored to have found actually were the things they claimed? Why are there so many cannonballs but no bullets? Why was the Sag fortified with not one, but two fortifications? Could it be the legends might inadvertently be true?

Our search for the answers continue, but we need the help of the residents of Palos. If you've found something that may be an artifact of our Indian or European predecessors, please contact the Palos Hills Historical Commission through William Potter, 8811 W. 102nd St. Palos Hills, who will make arrangements to have your find identified. Too much valuable information on our history has been lost forever. Perhaps you have the missing piece that will enable us to finish this chapter in the history of Palos Hills.